zen had two parents, buddhism and daoism. buddhism gave it the theoretical foundation. daoism gave it a paradoxical chinese character, the subtle attitude of Laozi.

“Like a fish hidden in a spring:” The Dao De Jing*of Laozi and its influence on Chan

*(We should all be using the pinyin system of transliteration now, so, though the Dao De Jing is better known in English speaking countries as the Tao Te Ching and Laozi is better known as Lao Tsu, I shall spell in pinyin, though translations will be quoted accurately as originally spelled).

Daoist ideas permeated all aspects of Chinese life before Buddhism arrived in China: philosophy, science, medicine, arts, physical fitness, cooking, agriculture and governance were all seen in terms of Daoist principles of constant change, the balance of yin and yang, and flow. When Buddhism arrived in China in the first century BCE, it was interpreted in the light of Laozi’s Dao De Jing.

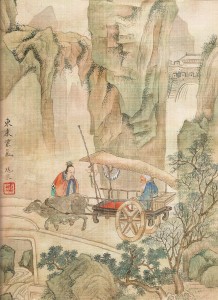

The sutras of the Buddha’s teachings are much studied and much admired in Chan, but let me also make a case for marvelling at the teachings of Laozi, which give Chan its distinctively playful style, quite different from the language of the Pali canon which can be dry and repetitive, as Hugh Carroll says. Laozi lived in China at more or less the same period as the Buddha lived in India, and each of them had vivid experience of the mystical vision. The Buddha was a brilliant intellectual and theorised his insight. Laozi was anti-intellectual and only reluctantly put his wisdom into words; words which were enigmatic and allusive. There is a much-illustrated story that he was leaving China through one of the Western gates and the gate-keeper, Yin Xi, refused to let him go until he had written down his wisdom for the Chinese to keep. The two of them are shown above. Laozi wrote the eighty one short chapters of the Dao De Jing, now the most translated book in the world.

The Dao

Laozi describes the Dao in Chapter 34:

The great Tao flows everywhere, both to the left and to the right.

The ten thousand things depend upon it; it holds nothing back.

It fulfils its purpose silently and makes no claim.

[Quotation from the Feng and English translation]

The Dao is nature’s flow. The word means ‘way,’ or ‘path,’ or ‘guidance,’ and seems to be used for the way of nature, the way nature is, and also the source of nature’s creativity. More prosaically it is just the way things are and the way they function. There is a way to fry a small fish, for example, and you’ll make a mess of it if you don’t have some care. Laozi scales this up.

Govern big countries

Like you cook little fish [Chapter 60, Addiss and Lombardo]

It is ultimately a mystery. The universe is there, life teems, everything changes – what is the mysterious way it works?

It is like the mother of all under heaven,

But I don’t know its name –

Better call it Tao.

Better call it great. [Chapter 25]

Laozi is careful not to define it as a philosopher would. He says that it cannot be known, and that the word Dao does not capture it. The closest he can get is a tautology:

Tao follows what is natural.

‘What is natural’ is the Chinese word for nature, ziran, which David Hinton tells us is made of symbols meaning ‘self-generating’ or, more vividly, since the ideogram for fire is part of it, ‘self-ablaze.’

The Dao is the underlying self-generating order of the universe and the original creative source of all things. This Chinese view is an energetic, unified, harmonious, temperate, continuously changing vision of nature (unlike the angry thunder and lightning gods of the Greeks or the merciless sun gods of the Middle East); and Laozi goes on to say that our attitude should be to follow its lead, to accept it as it is, to harmonise with it, and not to try and control or dominate nature.

The universe is sacred.

You cannot improve it.

If you try to change it, you will ruin it.

If you try to hold it, you will lose it. [Chapter 29].

And his images for the way to harmonise with nature start with water:

Best to be like water,

Which benefits the ten thousand things

And does not contend.

It pools where humans disdain to dwell,

Close to the Dao…

Only do not contend,

And you will not go wrong.

[Chapter 8 in the Addiss and Lombardo translation]

In Chapter 28 Laozi commends feminine and childlike qualities:

…keep a woman’s care!

Be the stream of the universe!

Being the stream of the universe,

Ever true and unswerving,

Become as a little child once more. [Feng and English translation]

The Dao will nourish one and have a good curative effect if one respects its subtle workings.

Tao is empty –

Its use never exhausted .

Bottomless –

The origin of all things.

It blunts sharp edges,

Unties knots,

Softens glare,

Becomes one with the dusty world. [Chapter 4, Addiss and Lombardo]

Adam, a member of the Portsmouth Chan group, explained this perfectly: “The practice of meditation has blunted my sharp edges, untied my knots and softened my glare,” he said.

Everything changes. Language tries to subdivide the flow and freeze the movement. Laozi is sceptical, wary of naming the parts. He contrasts the Dao with things that can be defined by naming, in the very first words of Chapter 1:

The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao.

The name that can be named is not the eternal name. [Feng and English]

And he goes on to elaborate an argument that associates the naming of things with a separation from the source, a distancing from reality’s mobile suchness. Naming, and all the labelling and discriminating that language use implies, is a kind of possessiveness, a control mechanism, leading to the human desire to own, to cling (a theme that exactly matches the Buddha’s insights, and the Buddha’s emphasis on how things are perceived or misperceived):

The nameless is the beginning of heaven and earth.

The named is the mother of ten thousand things.

Ever desireless, one can see the mystery.

Ever desiring, one can see the manifestations.

But he avoids making this contrast into a great universal dualism:

These two spring from the same source but differ in name…

The gate to all mystery.

There is a health warning with the Dao. Laozi seems to write of it as an ultimately unknowable ineffable mystery. Or does he? Perhaps he is making the more limited point, not that it is ineffable, but that language cannot capture it. He is laconic, and sometimes obscure in writing about it. But he implicitly gives it some attributes: integrity, wisdom and healing power. Is it an active agent in the world?

Tao hides, no name.

Yet Tao alone gets things done. [Chapter 41 Addiss and Lombardo]

Is it nearly a god? At one point he tells us,

The Tao begot one.

One begot two.

Two begot three.

And three begot the ten thousand things.[Chapter 42]

but never says any more about this, and changes the subject immediately:

What others teach, I also teach; that is:

“A violent man will die a violent death!”

This will be the essence of my teaching.[Chapter 42]

so it is difficult to see what he means by one, two, three and the ten thousand things. It is wide open to wild interpretations. Some have founded a religion on this and worshipped the Dao. There are superstitious Daoist cults in China today. Some have seen it as a philosophical origin myth like Plato’s Timaeus, with a Creator, a Demiurge, and junior gods. But judging by all the rest of the Dao De Jing, most interpreters see it as another way of saying that the Dao is a word pointing to the phenomenon of self-generating growth and change in all things: the ten thousand things are manifestations of nature’s way, arising mysteriously out of what a mystic perceives as a unity. Laozi specifically cautions against worshipping it.

The Chan teachers of the Golden Age of Zen, a thousand years after Laozi, often use the word Dao for the spiritual path or the way of practicing. They use other terms for the indefinable mystery at the core of things and absolutely refuse to turn it into an idea by defining it. Bodhidharma uses ‘mind’ (“This mind has no form or characteristics, no cause or effect, no tendons or bones. It’s like space”). Huineng uses ‘Essence of Mind’ (“Our Essence of Mind is intrinsically pure; all things are only its manifestations”). Huang Po, Linji’s teacher, uses ‘One Mind’ (“All the buddhas and all sentient beings are nothing but One Mind, beside which nothing exists. This Mind, which is without beginning, is unborn and indestructible.”) Linji warns against naming, “…the mind ground. If you can get it, use it, without putting any more labels on it”. He also, like Laozi, warns against treating it as sacred. Many of the protagonists of the koans collected by Hongzhi and Mumon use the term ‘Buddha nature,’ as in the famous first koan in The Gateless Gate, “Does a dog have Buddha nature or not?” The answer “No,” is the health warning: do not interpret the Dao or the Buddha nature as an idea, as something sacred, or as anything distinguishable from all that is in nature.

The greatest Chan teachers sound very like followers of Laozi when attempting to articulate a response to the mystery of ziran: “If you try to grasp Zen in movement, it goes into stillness. If you try to grasp Zen in stillness, it goes into movement. It is like a fish hidden in a spring, drumming up waves and dancing independently.” (Linji) It is impossible to say anything at all more than the tautology of Laozi: it is a mystery; nature is nature. “There is something in the world that is neither in the sphere of the ordinary nor in the sphere of the holy. It is neither in the realm of the false nor in the realm of the true.” (Wuzu)

Chan literature, following in the wake of the Prajna Paramita sutras, is philosophically sceptical about what can be known, or proved, in logic: there is nothing that can be asserted about the mysterious reality of nature. You cannot characterise it or list its attributes. The Chan adepts are more muted and cautious than Laozi when writing about what he called the Dao, and they call Mind or Buddha nature, but they have not jettisoned the Dao.

The Ethics of the Dao de Jing

Laozi is sceptical about those who trust words for fixing the ten thousand things in their place. Equally, he is sceptical about theory; he distrusts scholars and intellectuals. And he is very sceptical about public preachers and political moralisers:

When the great Tao is forgotten,

Kindness and morality arise.

When wisdom and intelligence are born,

The great pretence begins. [Chapter 18]

Laozi’s jaundiced view of most moralising reveals a much more nuanced sensitivity to the complexities of moral behaviour than, “Do not steal.” He tells us not to collect treasure and stealing will cease. Not to glorify heroes and people won’t be so quick to fight. It is a morality grounded in a feeling for what is natural, and not too clever (he does not trust cleverness), and a deep distrust of claims to virtue, of spiritual pride. Things have gone wrong if you need to point out the virtues, thinks Laozi. More than that, he sees that rule-bound morality and categorising actions into good and bad may do more to exacerbate problems than to solve them. In Chapter 38 he writes that benevolence is the next best thing if Dao is lost, but that after that there is a decline into righteousness and once that is lost there is only propriety.

Chan master Dahui later wrote in similar style, “Good and bad come from your own mind… When your mind is clean and clear, all entanglements cease… Both substance and function are in their natural state… your own mind’s marvellous function of change and creation… enters into both purity and defilement without being affected by or attached to either.” This is a morality that tiptoes through the world, accepting nature’s way, not trying to control anything and suspicious of category labels such as bad and good. It sees the system, with multiple causes and conditions, all interrelated. It is very different from the rule-bound ethics, proscribing a wide range of human behaviours, that came out of Indian monasticism, or, for that matter, the rule-bound commandments of Christianity, marinated in punitive notions of sin and evil. In ethics, the Chinese Chan teachers like Dahui follow Laozi more naturally than they follow Indian Buddhist monastic rules.

Wu wei and the De of the Sage

For people to harmonise with the flow of nature and act with authentic good feeling they must not strive too hard, or try to wrest control with energetic power. The ideal is wu wei, effortless action that goes with the flow, “nothing acting,” and it is another of the great themes of the Dao De Jing.

Non-doing – and nothing not done…

Make the least effort

And the world escapes you. [Chapter 48, Addiss and Lombardo]

Act and you ruin it.

Grasp and you lose it. [Chapter 64]

Simon Child teaches that, “Enlightenment is being out of the way.” Wu Wei is being out of the way, in the sense of not making the least effort to force the result, not acting with an ulterior purpose, an agenda, not grasping.

For Laozi, ‘the Sage’ is a major literary theme, as it is centuries later in the writings of the Chan masters of the Golden Age of Zen. The characteristic way of being of the enlightened person is described: Laozi tells us in the beginning, in Chapter 2, that,

…the Sage is devoted to non-action…

Lives but does not own,

Acts but does not presume,

Accomplishes without taking credit. [Addiss and Lombardo]

The Buddha made the same point: ‘My practice,’ the Buddha said, ‘is the nonpractice, the attainment of nonattainment.’

In the far East, Laozi himself has always been recognised as the archetypal Sage, the model of the enlightened man.

I take no action and people are reformed.

I enjoy peace and people become honest. [Chapter 57, Feng and English]

…the Sage is sharp but not cutting,

Pointed but not piercing,

Straightforward but not unrestrained,

Brilliant but not blinding.[Chapter 58]

‘The Sage’ is a Daoist subject which the early Chan literature dwells on at length. All the writers give accounts of how enlightenment transforms a person, and use fulsome imagery for the great skills of the sage. “Zen adepts just remain free, and are imperceptible to anyone… They walk on the bottom of the deepest ocean, uncontaminated, with free minds…” writes Yuanwu. In a beautiful passage, Hongzhi writes, “The worldly life of people who have mastered Zen is buoyant and unbridled, like clouds making rain, like the moon in a stream, like an orchid in a recondite spot, like spring in living beings. Their action is not self-conscious, yet their responses have order.” ‘Action that is not self-conscious’ would be a perfect definition of wu wei. Hongzhi is heir to Laozi and Dogen is heir to Hongzhi. Dogen studied with Hongzhi’s successors at Hongzhi’s Tiantong monastery.

Dao De Jing means the classic of Dao and of De (Te, in the Wade-Giles transliteration). “De” is the Dao as a guide to action; how to respect the subtlety of the way things are and harness the integrity, the wholeness, of Dao. De is “virtue” in the sense of a quality, and also somewhat in the Greek sense of power or inner energy. It is acting like a sage, guided by Dao, wu wei style, without presuming, without desire, without a personal stake in the game. The model is a good parent:

Tao bears them and Te nurses them…

Bears them without owning them

Helps them without coddling them,

Rears them without ruling them.

This is called original Te. [Chapter 51, Addiss and Lombardo]

In Chapter 49 Laozi says,

People who are not good

I also treat well:

Te as goodness.

Untrustworthy people

I also trust:

Te as trust. [Addiss and Lombardo]

In Chapter 68 he outlines the “Te of not contending:”

The accomplished person is not aggressive.

The good soldier is not hot-tempered.

The best conqueror does not engage the enemy.

The most effective leader takes the lowest place.

This is all of a piece with Laozi’s way of appreciating the power of water to wear down stone, the strong grip of a baby, the usefulness of the empty space in a bowl, the effectiveness of feminine qualities. Go with the grain. Respect the nature of things. There is a way to clean and fry a small fish without charging like a bull at a gate. And don’t be clever:

Ruling through cleverness

Leads to rebellion.[Chapter 65].

The Daoist inheritance in Chan Buddhism

The teachers who founded Chan, from Bodhidharma in the fifth century to Hongzhi in the twelfth century, took from the traditions of both sages, Laozi and Sakyamuni Buddha, and from Mahayana philosophers of the first and second century, to blend a Daoist Buddhism. The theorising and moralising of early Indian Buddhism were dropped. Meditation, as an individual’s inner path, or Dao, to discover truth for him or herself, became the central and only practice. ‘Mind’, or ‘Essence of Mind’, or ‘Buddhanature’ was the focus of their writings, as ‘Dao’ had been the focus of the Dao De Jing. Chan masters express hardly any interest in mainstream Buddhist ideas like suffering, rebirth, karma, meritorious deeds, ritual, scriptural knowledge and fussy ethical rules. Impermanence, on the other hand, which had always been at the heart of the Daoist account of nature, a continuous flow of changes seen in terms of yin and yang qualities in a dance of sixty four hexagrams symbolising decay and regeneration, was a strong theme in Chan. “The murderous demon of impermanence is instantaneous,” wrote Linji. “It does not choose between the upper and lower classes, or between the old and the young.”

The Buddha’s teaching of anatta, no permanent self, now deepened and extended by the Mahayana debates on sunyatta, the emptying of self, and the absence of self-essence, was at the very centre of the Chan vision. Bodhidharma’s, “Vast emptiness, nothing holy!” set the tone for China.

Chan is a distillation of Buddhist theory into practice and paradox. Philosophical Indian Buddhism gave Daoism a much firmer foundation in a theory of perception and a theory of conditioned causation. From that solid base, Chan could afford to indulge the subtle watery spirit of the Dao. Laozi’s Daoism had several features which were retained in Chan. And as we have seen, there are Chan themes that were present in different proportions in both the Buddha’s and Laozi’s teachings.

The stripping out of inherited conditioning in order to clear the mind is a great theme of the Buddha’s teaching. “Luminous, monks, is the mind. And it is defiled by incoming defilements,” he said. How to drop the defilements clouding the mind remained absolutely central to Chan teachings of the Tang dynasty. But Laozi also touched on this aspect of mind. The Dao De Jing tells us in Chapter 33 that:

Knowing others is intelligent.

Knowing yourself is enlightened.

and in Chapter 48 that wu wei is the process:

Pursue knowledge, gain daily.

Pursue Tao, lose daily.

Lose and again lose,

Arrive at non-doing.

Non-doing – and nothing not done

Letting go. Unlearning. Losing. These were Daoist themes but the Dao De Jing did not spell out what one must unlearn. In the Buddha’s teaching it was explicit: conditioned responses of attraction and aversion; all judgements and conditioned ideas. Clearing the mind is the topic that dominates the writings of the Tang and Song dynasty Chan masters. They develop what are only hints in the Dao De Jing, but much more substantial analysis in the Pali Buddhist sutras, into the core of their teaching. One or two quotations from any number will be sufficient to make the point, starting with Seng Tsan’s, “Simply avoid picking and choosing,” through Huang Po’s, “If you students of the Way desire knowledge of this great mystery, only avoid attachment to any single thing beyond Mind,” and coming to Yuanwu’s, “Shed views and interpretations that are based on concepts such as victory and defeat, self and others, right and wrong. Thus you pass through all that and reach a realm of great rest and tranquillity.”

Hui Neng was the founding father who preached it: “The mind should be framed in such a way that it will be independent of external or internal objects, at liberty to come or go, free from attachment and thoroughly enlightened without the least beclouding.” He summed up: “…so far as we get rid of all delusive ‘idea’ there will be nothing but purity in our nature.”

Conclusion

Chinese Daoist anti-philosophy was the mother of Chan; Indian Buddhist philosophy was its father. The child of these two inevitably has a sense of subtlety, a sense of humour and a sense of paradox. Chan is a Daoist form of Buddhism with Chinese characteristics. The Dao De Jing is more mystical, mysterious, poetic and enigmatic than the Pali sutras. It is a foundation text for my Zen.

Translations:

Tao Te Ching trans. Gia-Fu Feng and Jane English, London, Wildwood House, first published 1973.

Tao Te Ching trans. Stephen Addiss and Stanley Lombardo, Boston, Shambhala, first published 1993.