In the first decade of the 20th century, poetry in English sounded like this:

Lovely in dye and fan

A-tremble in shimmering grace,

A moth from her winter swoon

Uplifts her face

And W.B.Yeats wrote rhythms like this:

Wine comes in at the mouth

And love comes in at the eye;

That’s all we shall know for truth

Before we grow old and die

In 1914 and 1915 some strange translations were published. A new note was sounded and a fresh branch of modern poetry was born:

The autumn wind blows white clouds

About the sky. Grass turns brown.

Leaves fall. Wild geese fly south.

And:

While my hair was still cut straight across my forehead

I played about the front gate, pulling flowers.

You came by on bamboo stilts, playing horse,

You walked about my seat, playing with blue plums.

And we went on living in the village of Chokan:

Two small people, without dislike or suspicion.

Formally, they are in unrhymed free verse. The language is plain and direct, and the imagery, if it is imagery, is real observation, not constructed metaphor representing something else. First and foremost it is ‘the thing in itself’. A Westerner would write, “My love is like a red, red rose.” An East Asian poet would write about a rose. Perhaps, as the after-taste of the poem, there would be a fragrance of romance, but the poem would be about a rose.

The poems were ‘translated’ by an American, the secretary to W.B.Yeats, working in Sussex, using a crib prepared for him by an American art collector who had interviewed Japanese professors about the literal meanings of the characters in classical Chinese poems. Neither the art collector nor the ‘translator’ knew Japanese or Chinese, and neither of them had the original Chinese sounds to work from: they had the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese words. The ‘translator’ was Ezra Pound, and he had only a hazy idea of how highly rhymed and structured the originals were in Chinese. Nor did he know how to understand the tonal pattern of Chinese verse, a complexity that has no equivalent in our language, though he later studied it and tried to represent it by chanting and singing. So for these translations he simply ditched the rhyme scheme, the Chinese rhythmic structure, the tonal patterning, and any attempt to represent accurately the connotations of the poet’s language, and constructed his own new versions using the story of the poem, and the simple imagery of the poem, as he was able to piece it together from the notes. The effect was very striking. It liberated English verse at a stroke.

For all that he did not know much about Chinese language or verse structures, Pound did indeed understand the Sino-Japanese attitude to imagery. He had seized upon it and launched a new literary movement in London in 1913 with a manifesto and an anthology of “Imagisme”. Imagist poets were exhorted to write, “Direct treatment of the “thing”, whether subjective or objective”, to waste no words, eschew adjectives, and to compose in musical phrases. The newly composed Imagist poems baffled people and did not have a great impact, but when Pound published his Chinese ‘translations’ the impact was immediate. The “new, plain-speaking, laconic, image-driven free verse” (Weinberger) which was the origin of modernism in English poetry, had arrived. An emperor’s concubine writes:

O fan of white silk,

clear as frost on the grass-blade,

You also are laid aside.

One sees the fan, a real fan, ‘the thing in itself’, and only faintly, as an after-taste, the emotion of the abandoned favourite.

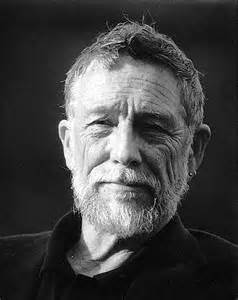

Ezra Pound was the great impresario of modernist poetry. Pound promoted James Joyce, and inspired the Americans Ernest Hemingway, Robert Frost and William Carlos Williams.

He helped T.S.Eliot with The Waste Land, cutting it to make it more laconic and leave the images to speak for themselves. He encouraged Arthur Waley, a real Chinese scholar, to translate the Chinese classics. Waley’s first book of 170 Chinese poems, published in 1918, was a sensational success. More translators piled in and a wave of books of Eastern verse hit the English-speaking world.

The new publications revealed the hinterland of Chinese culture: a reverent attitude to the turning seasons and nature’s ecology; a Chan (Zen) Buddhist sense of simplicity in living, relishing a little hut, a cup of wine, and the full moon at the window; a weary mandarin’s cynicism about political life, the horrors of war, and his choice to retire as a hermit to the country; a love of wilderness and mountains; the ecstasy of the enlightened Chan sage.

These themes were particularly attractive to Americans still romantic about the frontiersman spirit, the rejection of the city, a life free from government interference, and the simple delights of the hermit. The themes communicated a heady sense of freedom, reinforced by the translation policy of using plain English free verse for what were originally elaborately wrought and highly structured Chinese poems. The beatniks of the fifties consciously modelled their lives on the Chinese Chan sages of the middle ages, turning their simplicities into a rebellion against the materialism of the modern world. The American poem became as informal and laconic as it was possible to be. And the new wave of translations from Chinese by Kenneth Rexroth, Gary Snyder, and, more recently, David Hinton and Charles Egan, are arguably the greatest of all modern poems in English, – though they are still not much like Chinese classics in form, more Poundian than Poian!

What a strange series of accidents, misunderstandings, leaps of the imagination, and inspired improvisations power cross-cultural creative surges! There’s a word for that, and it is ziran in Pinyin. It is the founding principle of ancient Daoist thought: “a constant burgeoning forth that includes everything we think of as past and future… here lies the awesome sense of the sacred in this generative world: for each of the ten thousand things, consciousness among them, seems to be miraculously burgeoning forth from a kind of emptiness at its own heart…” (David Hinton, in his Introduction to Mountain Home, the wilderness poetry of ancient China).