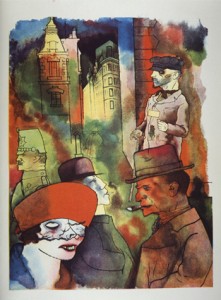

The intolerant fanaticism in this face reveals a mind driven by anger and hatred and ignorance. The ‘three fires’ of Buddhist teachings are perfectly illustrated in George Grosz’s faces. Samsara in the Buddha’s teachings is the world of the unenlightened, as perceived by those people unable to escape craving and anger, and unwilling to accept impermanence. The Buddha described, “…beings wandering and running around, enveloped in ignorance and bound down by the fetters of thirst.” George Grosz was not illustrating this proposition consciously, but his eye, soured by his experience of the First World War and the gross inequalities of Weimar Berlin, skewered suffering humanity, struggling with its primitive drives and passions, and lost without any more noble conception. Here they are:

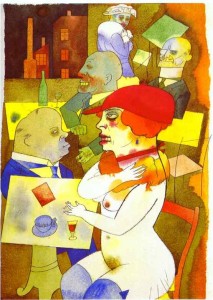

These are people with no self-awareness, drowning in the waves of samsara. If ever a painter expressed the debilitating effects of desire it was surely George Grosz. His is a complete dharmic vision of lives lived in a state of haunted ignorance, in a frenzy of craving for what can never satisfy. The woman in a red hat with one rolling eye is the epitome of delusional suffering. She is not going to find her fulfilment like this, craving for what you cannot keep. But all his people are lost, confused; animals driven by crude appetites.

Bigots:

Murderers:

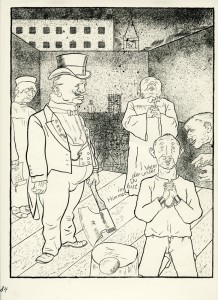

And a power structure of ignorance, brutishness and hypocrisy:

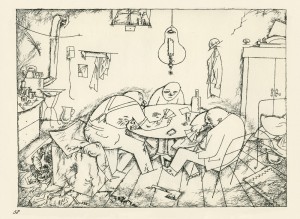

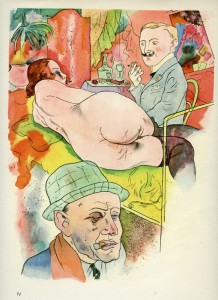

It is not clear how Grosz views the victims: the beggar and the man about to be beheaded, but only one character in the whole series of prints appears to have any perception of the ways in which people are tormenting themselves with futile desires and hostile passions, and he is also deeply compromised in his self-awareness:

It is a self-portrait of Grosz, but Grosz was only in his twenties at the time and portrays himself as an older man, and one who seems to know the terrible appeal of consuming sexual passion.

I use the terms samsara and dharmic about this vision, but Grosz would not have had a Buddhist world view. At the time he would have happily called himself a Dadaist, and, with less confidence, would have acknowledged himself a bit of a Communist. In hindsight, in his autobiography A Small Yes and a Big No, he wrote, “My own hopes were never vested in the masses… What the masses had in plentiful supply was hatred, fear, oppression, deceit, derision, smut and calumny… I had lost all hope in the ‘lower’ classes and, in any case, had never joined in the beatification of the proletariat, not even at times when I pretended to certain political views. The war was a mirror;” [he is writing about the period 1916 to 1922] “it reflected man’s every virtue and every vice, and if you looked closely, like an artist at his drawings, it showed up both with unusual clarity.”

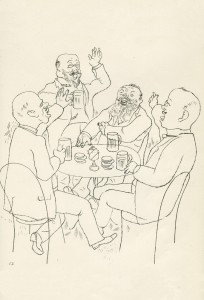

He described the war as “four horrible years” which filled him with “utter disgust.” I think his perception of this manic samsara was not so much politically shaped, and certainly not shaped by Buddhism, but revealed to his mercilessly accurate artist’s eye in a particularly febrile time and place. First, the artist’s eye: “I began to draw from nature in the Japanese style, that is I made quick little sketches of people walking about, reading newspapers, eating in cafés and anything else that appealed to me.”

Berlin in the aftermath of the war was the place, and he writes about it with loathing: “The times were certainly out of joint. All moral restraints seemed to have melted away. A flood of vice, pornography and prostitution swept the entire country… Men in white shirts marched up and down, shouting in unison: ‘Up with Germany! Down with the Jews!’ They were followed by another group, also in disciplined ranks of four, bawling rhythmically in chorus: ‘Heil Moscow! Heil Moscow!’ Afterwards some of them would be left lying around, heads cracked, legs smashed and the odd bullet in the abdomen… The city was dark, cold and full of rumours. The streets were wild ravines haunted by murderers and cocaine peddlers, their emblem a metal bar or a murderous broken-off chair leg.”

His historical perspective is apocalyptic: “As the geo-politicians stepped into the shoes of the humanists, the enlightened age that had begun with the Renaissance ground to a halt, and the age of a blind, ironclad ant, completely indifferent to the fate of individuals, the age of numbers without names and of robots without brains, came into being.”

His artist’s eye, as one can see in his self-portrait, was sharp, ruthless, but deeply implicated and painfully aware. “I made careful drawings of all these goings on, of all the people inside the restaurant and out, deluding myself that I was not so much a satirist as an objective student of nature. In fact, I was each one of the very characters I drew, the champagne-swilling glutton favoured by fate no less than the poor beggar standing with outstretched hands in the rain. I was split in two, just like society at large.”

I do not claim that Grosz was promoting my Buddhist understanding, but I say that his portrayal of the unsatisfying world people create of their craving/desire, hatred/anger and delusion/confusion, as described by the Buddha, is unsurpassed. He had the eye, educated by disgust at the war, and contempt for the political degeneration of his times, the greedy wealth and horrible poverty, and he had the wonderful skill to set it all down so that we can actually see what is going on in the minds of these suffering characters, imprisoned in the human condition without understanding it. His own collusion makes it all the more poignant. He is not outside sneering, but inside, grinding his teeth.

Paramita

Nirvana

Grosz made some furious collages . But as his drawings at the Richard Nagy gallery attest, he was a hugely gifted draughtsman.