The Hsin Hsin Ming by Seng T’san is full of bracing shocks. “Try not to seek after the true,” it counsels. (What?) “Only cease to cherish opinions.” (Eh?)

The “one great barrier of our faith,” Joshu’s MU koan, is a meditation upon “Nothing,” an invitation to stop clinging to all the somethings that one believes, the cherished opinions, and to float free. It is a hard path, to relinquish deeply rooted cultural ideas. Mumon instructs, “make your whole body a mass of doubt… Gradually you purify yourself, eliminating mistaken knowledge and attitudes you have held from the past.” In our own English culture is there any equivalent to this stripping down of all one’s cherished beliefs to discover enlightenment?

London’s great mystic engraver-poet William Blake, late in his life, in 1817 when he was sixty, illustrated The Book of Job as part of his ambitious project to offer, “The Bible of Hell, which the world shall have whether they will or no.” His modest plan was to rescue the Bible from the priests and moralisers and recreate it as a call to imaginative transcendence, thereby redeeming Western civilisation! His radical re-interpretation of The Book of Job culminates in a MU-like recognition. In Plate 11 of the 21 plate series of engravings, Job in his despair confronts his own notion of holiness and realises with a terrible shock that he has projected himself into his false picture of a cruel God. Later plates in the series explore the implications of this insight for his view of the world and his new sense of a human and humane divinity.

The Bible story starts with God and Satan having a bet. Satan bets that if he torments Job enough Job will curse God. God bets that Job will remain constant. The horrible torment duly unfolds, and Job is brought to the point of despair, to curse the day he was born, and to complain of God’s injustice. Job’s friends are “miserable comforters” who argue that Job must have deserved his suffering. God’s ways are mysterious but he must be right whatever tortures he inflicts. A debate about the justice of God’s cruelty ensues, a grim theme, but adorned with some of the most memorable poetic phrasing in the King James Bible.

Blake re-interprets this story in the light of his mystical vision, deconstructs the ghastly God character that Job and his friends believe in (“God is only an allegory of Kings,” Blake had written), ignores the fruitless debate on the justice of suffering, and rejects the morality of cruel punishment. Blake replaces Job’s conception of God as an internalised authoritarian parent or ruler, a self-projection of disgust, with the words of Christ in the St. John gospel: “Ye shall know that I am in my father and ye in me and I in you… If ye loved me, ye would rejoice…” Blake took these sentences seriously. He believed that, “God only Acts & Is, in existing beings or Men.” In his combative way, he proclaimed that, “those who envy or calumniate great men hate God; for there is no other God.” “…men forgot that All deities reside in the human breast.” “There is no other God than the God who is the intellectual fountain of Humanity.” What people all over the world are really praying to, he asserts in The Divine Image in Songs of Innocence, is “the human form divine.”

For Mercy has a human heart,

Pity a human face,

And Love, the human form divine,

And Peace, the human dress.

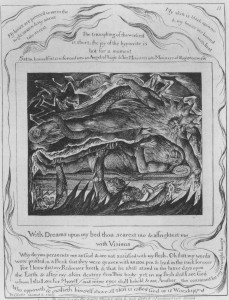

Twenty five years before his Job designs Blake had coined his phrase “mind forg’d manacles” for the ignorance of people who need to be liberated from their rigid and repressive ideas. Plate 11 shows Job affrighted with a nightmare, chained by devils, when his God appears to him. Blake uses this psychic drama to reverse the values of the Bible story and show the moment when Job realises that the God he has worshipped is a mirror image of himself, with a cloven hoof and a serpent body, bullying him with the tablets of the law. Blake finds an apt quote from St. Paul: “Satan himself is transformed into an Angel of Light and his Ministers into Ministers of Righteousness.” In Blake’s vision, this is a trick with which Job has tragically fooled himself, and by implication one with which the Christian church has also fooled the faithful of Europe; they have turned a loving sense of the holiness of life into a monster of authoritarian control.

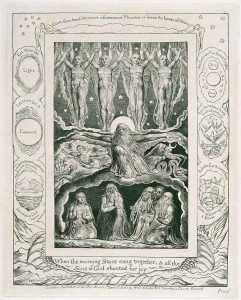

What follows this realisation? “Suddenly Mu breaks open,” writes Mumon. “The heavens are astonished, the earth is shaken… At the very cliff edge of birth-and-death, you find the Great Freedom.” The way that Blake represents this new freedom is to quote from The Book of Job its wonderful language for the greatness of God, which we Chan practitioners would call koans of Suchness: “Hath the rain a father? or who hath begotten the drops of dew? … Canst thou bind the sweet influences of Pleiades, or loose the bands of Orion?” And in Plate 14 Blake illustrates a phrase from Job, “When the morning Stars sang together, and all the Sons of God shouted for joy.”

The torment is over. Job finds joy in the creation again. The terrible storm in his head caused by clinging to a brutal and controlling vision of God, and trying to justify hideous sufferings as the work of God, has been relinquished. Blake’s Job is released into a new relationship with the world around him, which Mumon would call Great Freedom. “Only cease to cherish opinions,” wrote Seng Ts’an, and D. T. Suzuki wrote: “The essential discipline of Zen consists in emptying the self of all its psychological contents, in stripping the self of all those trappings, moral, philosophical and spiritual with which it has adorned itself ever since the first awakenings of consciousness. When the self thus stands in its native nakedness, it defies all description.”

Blake had seen the world like this, stripped of its trappings of belief and unclouded by conditioned perceptions. His insight was that, “Everything that lives is holy.” That the body and the soul are not distinct. That, “Energy is Eternal Delight.” That, “If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite.” Mumon described this infinite, which he called the Great Freedom: “…you enjoy a samadhi of frolic and play.”

I wish poor Blake, soldiering on unappreciated and alone against the armies of ignorance, could have read Mumon and Seng T’san. He would have understood instantly. He would have laughed with delight.

George Marsh 2013